Last June, a BBC film crew joined Memorial University's Autonomous Ocean Systems Lab on an iceberg survey expedition to shoot a segment on icebergs for their 'Forces of Nature' documentary series. The resulting 10-minute piece was recently screened in the UK as part of the first episode, entitled 'The Universe in a Snowflake' (see previous posts). Although not officially a VITALS project (the normal topic for this blog), the expedition did involve a glider as well as some VITALS contributors, so is a justified diversion. Here's what went on behind the scenes...

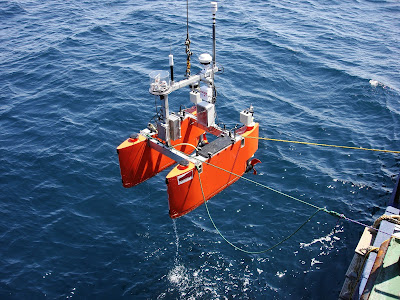

Loading our iceberg profiling glider.

The front end of the glider has been modified to hold a scanning sonar to measure the underwater structure of bergs. The glider also uses this sonar to autonomously circumnavigate around bergs, maintaining a predetermined distance from the sides.

Our main expedition vessel, Shamook.

Ocean currents and winds bring bergs into the shallow bays of Newfoundland where they can become grounded.

Large icebergs show up on radar. Here you can see one just below the cross at the top left of the screen.

We've heard tales that grounded bergs can bring a chill to nearby coastal towns by the cooling onshore winds.

An iceberg-chilled coastal town?

Wavecut notches are a common feature of bergs. Submerged ice melts the faster than the ice above water, with erosion being strongest at the waterline. This can lead to bergs becoming top heavy and rolling over to reestablish equilibrium. Large submerged protrusions called rams can break off in the process.

Sometimes you can see multiple wavecut notches, as on the right of the photo here. These reveal how the waterline has shifted as the berg has changed orientation. A cleaved surface develops above these notches where chunks of ice become undercut and fall off. Note the black sediment, possibly bedrock scoured out while the ice was still part of a glacier.

The profile of this berg looks a bit like the Memorial University logo.

The film crew brought some nifty gadgets with them, such as this gyro stabilized camera system.

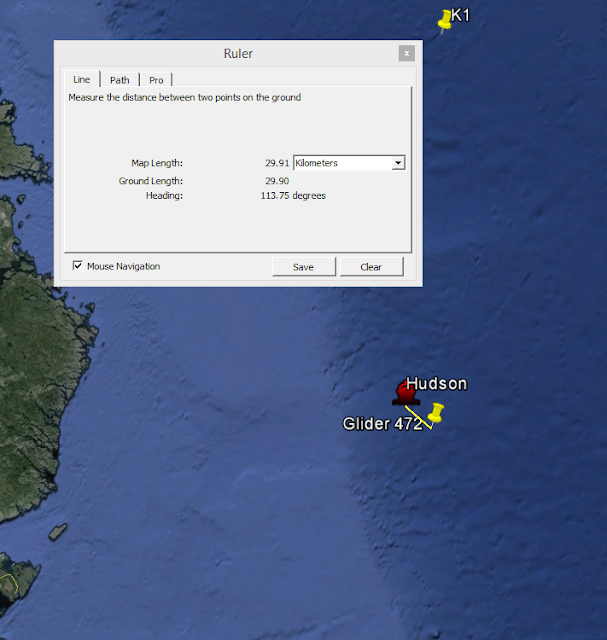

We had some nifty gadgets of our own, like this autonomous surface craft fitted with a radar and camera to capture the above-water structure of bergs.

Filming on small boats can get a bit crowded.

Scuba diving around icebergs is not for the faint of heart. As grounded bergs scrape around on the seabed, they can emit loud booms that the smiling underwater cameraman here (Doug Allan, second from left) said he could feel reverberating through his body.